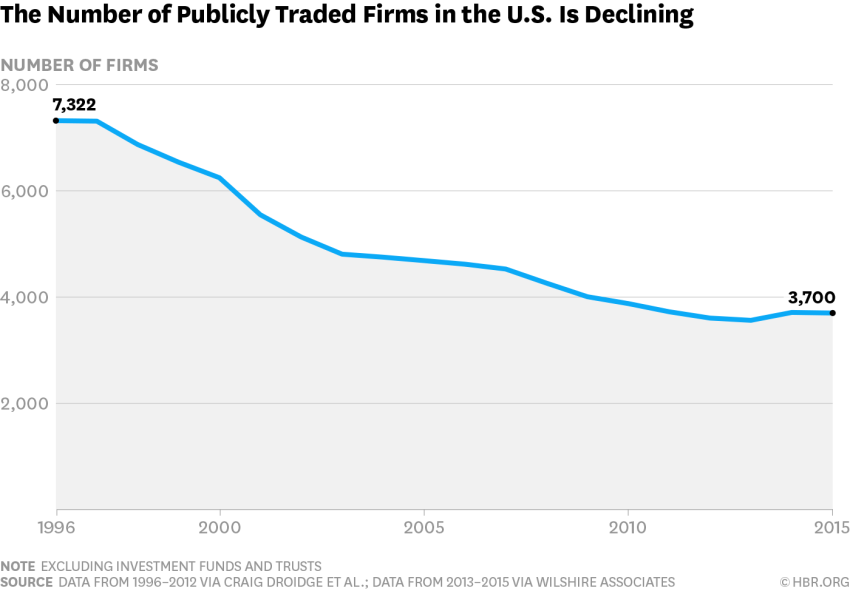

A silent, seismic shift has dramatically altered corporate ownership and business governance globally. From 1996 to 2015, the number of publicly traded companies in the United States alone dropped nearly 50%. Some of this ownership shift includes failure of firms or acquisition of firms into larger conglomerates (either domestic or foreign), but much of the de-listing shift comes from publicly traded firms becoming private.

A major catalyst for this shift has been private equity firms, which take companies private and incorporate them into their own portfolios. The types of private equity firms and the approaches to managing these firms has evolved over the last 40 years through three general phases. While in the first two phases, PE firms turned around the companies they acquired, we believe that in the newest phase the PE firms themselves are also being transformed.

Three Phases in the Evolution of Private Equity Investment

In phase one (buy and sell), PE investors looked for the equivalent of a “fixer-upper house” — a dilapidated company in a good industry that could be purchased at a discount and, after the business equivalent of some fresh paint and new appliances, resold for a profit. This phase was loosely called leverage buy out (LBO) from about 1979 to 1990 and included over 2,000 LBOs. These buy outs shifted agency from owners to managers; “corporate raiders” worked with high-yield debt to fund these turnarounds. The primary focus was on fixing the acquired firm through financial restructuring, dramatic cost cutting, and strategic slashing. Leaders were driven by short-term profits and rapid action to flip the organization.

In phase two (buy and hold), PE equity investors bought the fixer upper and repaired it, but then rented it and ended up loosely managing the house before selling it. This phase of mega-deals gave rise to large PE firms in the 1990s and 2000s that acquired and helped manage large firms. These “buy, fix, manage, and then sell” PE firms were essentially umbrella holding companies while the acquired firms would become better managed before returning to the public market. Large private equity firms (e.g., KKR, BlackRock, Blackstone) became publicly traded holding companies exploiting capital markets to expand their reach. Private equity partners created cadres of well-known leaders who could be installed into the newly acquired organization to manage it until the PE company was ready to sell. But just as rental houses are often given minimal maintenance, leaders of acquired firms brought in only the minimum leadership necessary.

In phase three (buy and transform), PE equity investors buy the fixer upper, but then decide if they want to turn it into a rental house or use the property for something else entirely (e.g., a condo development, apartment building, or golf course). In this phase, the acquired property is not just managed, but transformed.

How Phase 3 Is Changing PE Companies

In phase three, PE firms are not simply holding companies waiting to dispose of the property, nor are they operating companies seeking to integrate their acquisitions into an existing business. This phase of private equity work is a new organizational configuration in which independent businesses make up a portfolio, yet operate autonomously and can be spun off at any time. Though autonomous, they can improve their operating capabilities and speed up their time to reinvention by learning from each other. Following the real estate metaphor, the PE company is less like a house flipper and more like a property developer: each separate home is designed, built, bought, and sold as an independent property. But the planned urban development PUD also has shared infrastructure and systems that enable the community to operate (e.g., architectural design, streets, water, electricity, sewage, and regulations).

This shift means that PE firms’ approaches to talent and leadership must also change.

Traditionally, PE firms bring financial discipline and strategic clarity to firms they acquire. This expertise may include restructuring debt, increasing financial leverage, clarifying strategic priorities, increasing productivity, implementing rigorous operational systems, or heightening accountability for results. This expertise enables phase one (buy and sell) and phase two (buy and hold) to occur.

But for phase three (buy and transform), financial discipline is not an event, but a pattern; strategic clarity is not a direction, but a commitment; operational excellence is not a tool, but a mindset. That means that in this phase, PE firms also require expertise into leadership, talent, and organizational capabilities and culture. Acquired organizations have organization capabilities that have to be transformed and talent that must be assessed and upgraded.

Doing so will require PE firms themselves to add new capabilities and new talent. Private equity deal teams and the advisors they hire are well known for their expertise in gathering masses of data, crunching numbers, and measuring financial performance to predict future returns. However, in phase three traditional data gathering and traditional metrics are not sufficient to ensure significantly differentiated value creation. Research by accountants and economists, including Baruch Lev, has indicated that over 50% of the value of a firm cannot be explained by its financials and that new measures should be used to assess firm value. These measures will include intangibles like strategic clarity, customer connection, brand leverage, and R&D impact and leadership capital around competencies of individual leaders and capabilities of the organization as a whole like culture, talent, accountability, collaboration, and information. PE firms aimed at benefiting from a phase three strategy need to expand their data sources and deepen their ability to sift through both structured and unstructured data in order to find more predictive variables.

To succeed in a world where variables such as leadership, talent, culture, and reputation rival traditional financial performance and industry analysis, the industry needs new comparative benchmarks and tools to help make the intangible tangible

Now that many previously public firms are privately held and PE firms have shifted from buy and sell or hold to buy and transform, we see a new vista for data gathering, analyzing, and reinventing leadership and organization practices. As PE firms bring data-driven rigor to the assessment and development of leadership and organization practices, they will be better able to transform their acquired companies. Whilst PE’s shift is significantly impacting the increasing number of privately held companies, repercussions of PE’s silent revolution will impact everyone as PE firms become innovation incubators for insights on transformative leadership and organization.

By Dave Ulrich and Justin Allen

Source: Hbr.org (Harvard Business Review)

Barış Öney

Barış Öney